What I Learned about Past Pandemics from My Grandfather’s Memoir

(Guest Post by Sally Ito)

How has the pandemic affected your life? That is the question being asked of many of us today. When my plans to serve as writer-in-residence at Historic Kogawa House in April and May changed as the pandemic progressed around the world, other ways began to emerge that would allow me to reach readers with my words. One of the ways was to blog. I had hoped to share daily haiku on the Historic Joy Kogawa House blog and write about my experiences while living at the house. The West Coast was where my Japanese Canadian family had lived prior to the war, and Vancouver was where I had travelled from Alberta to study creative writing at the University of British Columbia. I wrote about this family history in my recently published memoir, The Emperor’s Orphans.

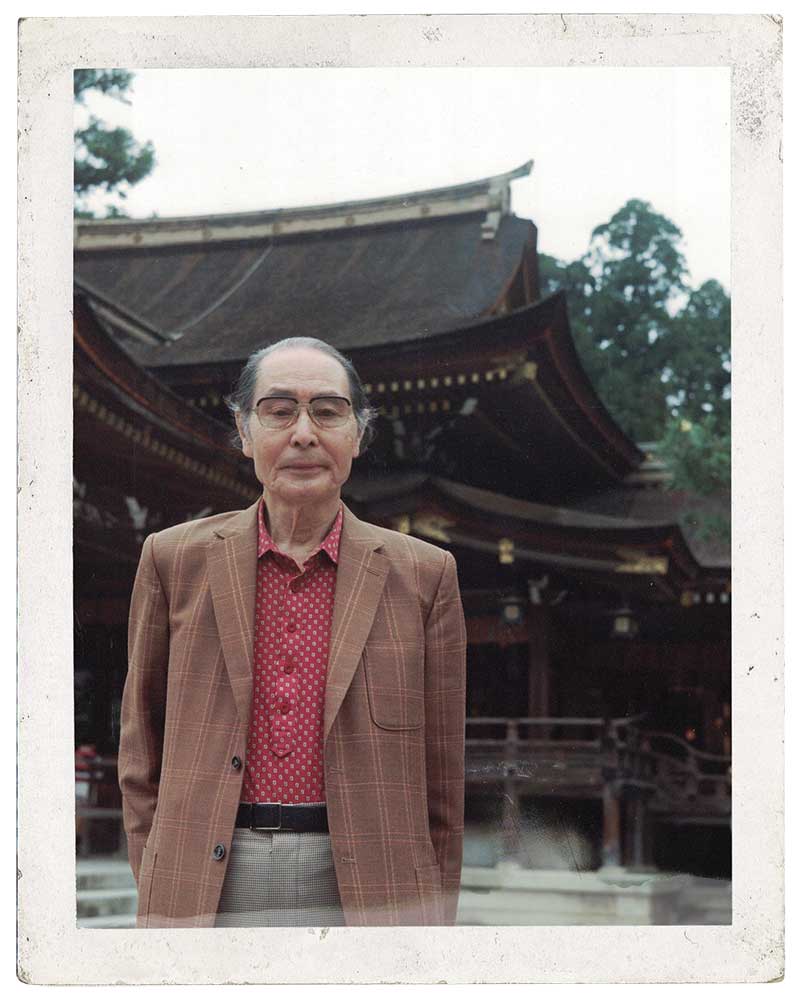

One of the storytellers in my book was my maternal grandfather, Toshiro Saito. For some years, I spent time translating his memoir into English. It was there that I discovered he contracted the Spanish flu in the pandemic of 1918–1919. As an adolescent who had just entered junior high school in Tokyo, contracting the disease changed his life. As noted in my prefatory comments to this section in The Emperor’s Orphans, I detected in this part of the memoir the solidifying of my grandfather’s voice and sensibility. Toshiro Saito was a thorough-going realist, not inclined to romanticism or to religion, even though he was attracted to the literary. His enthusiastic participation in the school literary magazine to which he turned his attention after his illness marks his early formation as a man clearly interested in the power of language on the printed page.

The passage from his memoir reproduced here recounts my grandfather’s days in junior high school before and after he contracted the deadly flu. It may interest readers today who are grappling with the ways in which the current pandemic is affecting their lives and their education, in particular.

Junten Junior High School Days

After finishing elementary school in Taisho 7 (1918), I went to Kanda to a private junior high school known as Junten Junior High School, located right next to Jimbocho. South of it was Shoka University (now known as Hitotsubashi University). West of it was Senshu University. East of it was Meiji University. The school was right at the centre of Kanda and had no campus grounds to speak of. When you entered the gate, you had to cross 600 tsubo (1,980 square metres) of hard dirt to reach the front of the two-storey building. Although the school had a concrete foyer on the ground floor where we gathered when it rained, there was no large field where you could do sports like soccer or baseball. The grounds were used strictly for calisthenics and military-style exercises. On festival days, we held simple amusement fair games and contests.

The school uniform had white gaiters. All students were expected to wear the white gaiters, and we were forbidden to remove them even if we were not on school grounds. At the gate, a senior student would stand on guard like a sentry, holding a rifle and bearing a sword at his belt. When a teacher passed through, the student would move his rifle away in a prescribed manner. Incoming students had to salute the guard before entering. The senior “sentry” student was dismissed right after school ended for the day. In this way, Junten resembled a military academy that would be hard to imagine nowadays. Because of this aspect of the school, many of its graduates went on to enter exclusive military and naval academies. Since the grounds of the school were so small, the brighter students may have gone straight home to study for their entrance exams instead of hanging around and playing. Average students probably would have indulged their passions in the movies (known as moving pictures at the time), and those truly interested in sports would find others like themselves and locate a gym or field suitable for their activities. As for me, I liked track and field, and so those of us interested in that sport used a track in Sugamo that was affiliated with Mitsubishi.

I also liked to play tennis. I often played in the courts of the big manor house belonging to my classmate Arimatsu. We would play against each other and sometimes with his older sister who was a year older than us. She would tie up her kimono sleeves to play, and while fluttering about, the red undergarment of her kimono would sometimes be exposed, the hem flipping up to show the whiteness of her ankles, and this sensual sight left a deep impression on me. All I recall of Arimatsu now was that his father was a politician, a member of the Diet.

The school’s sumo ring had four supporting pillars around it with a roof. The ring never got wet, so one could practise nearly naked, wearing only the requisite loincloth, even if there was rain.

Sumo was the only officially recognized sport at this school, and since my grandfather, like me, had been a great fan of the Grand Sumo Tournament, I enrolled in the sumo program. I did this more out of curiosity than anything because I wanted to try different things.

As I said before, many students had parents who were supporters of the professional sumo wrestlers that participated in the Grand Sumo Tournament, so as a club, we were allowed to practise at the professional stable of Deba No Umi. The first sumo wrestler to emerge from this stable was the great and strong yokozuna, Hitachiyama. With excitement, I wondered what kind of practice we would have in such a stable, the biggest of its kind in the sumo world at the time. As it turns out, we practised with the new novice recruits and the next level above them, who were made up of boys not much different in age from us. Of course, the professionals were incomparably stronger and had a different quality of strength in their moves, and although some of the members of our club won an occasional bout, on the whole our club was completely exhausted and worn out by the level of training that we experienced there. Even though we were clearly inferior in our skills, we were allowed to take baths with the wrestlers and have dinner with them before going home.

I had fair skin and so when we slapped each other about I had red marks all over my body. On seeing this, others would laugh and this bothered me a lot.

In the following year, 1919, the Spanish flu hit Japan and unfortunately I contracted the disease, as well as pneumonia. I was absent from school for a very long time, so obviously I couldn’t train for sumo anymore. After I graduated from grade eight, I got pneumonia again in the first term of grade nine. The previous time I was sick I had been hospitalized, but this time I was treated at home by a hired nurse and a doctor who came to check up on me periodically. I got better more quickly this way. I had the same doctor as before; he owned the hospital I was treated at the time. I think I was treated by him at home this time because at his hospital, I was put into a private room where the nurse had to stay with me all night. (As this was a private hospital, this was the policy they had for rooms.) Even though I was only a grade eight junior high school student, I was as tall as an adult man and had a sumo-trained robust youth’s build and probably appeared desirable to the young woman who was my nurse. She was of a ripe age herself so locking us together in the same room overnight was probably not a good idea, hence my doctor’s recommendation that I be treated at home this time.

Because of this illness, I quit sumo. From the last part of the first term of my third-year summer break, I began to study very hard. The person who helped me was the third year’s mathematics instructor whose name I forget; he was a graduate of Hokkaido Imperial University and was only teaching part time there because he aspired to write civil service examinations in hopes of working in the judiciary as a prosecutor, judge, or lawyer. At night, I would go to this teacher’s house, which was near Komagome Station, and catch up on subjects such as algebra and geometry that I had missed studying before because of the pandemic and my illness.

Although it may sound funny to put it this way, I would then repay my teacher’s efforts by helping him to study for his exams. He would borrow sample exams or reference books from his friends and I would read aloud from them questions that he then would write down.

He praised my oral read-aloud abilities, saying, “Your literary skills are very good and you will impress others with them.” He thought I was exemplary. And so it was that I was often loved by the teachers of my school.

After my two bouts of illness, I lost confidence in my health and was no longer interested in sports. At that time, there was in my class a literary-minded boy named Hashimoto Souji. Through his influence, I became enlightened about the world of literature. This may sound rather pompous, but he had memorized the poems of Shimazaki Toson and Doi Bansu, and he himself wrote beautiful poetry. And so I then too began to write poems. However, Hashimoto’s criticism was quite sharp so my inspiration withered. After that, I no longer had any interest in Japanese poetry. This was not only due to Hashimoto’s criticism. Although Bansui’s five–seven verse pattern has rhythm, poetic sentiment, and may be a “prose poem” if you may call it such a thing, it still does not appear to be true poetry to me in the way the poet cuts apart verses and arranges his lines.

Even in English and Chinese poems, there are rhymes, and so they are poems. If there is no rhyme, there is no poem, I believe.

Hashimoto died at the end of his third year. We became friends through poetry and at his funeral at his house in Mukojima, I lined up with the other mourners as our class representative. I think because he was a highly sensitive boy, he died young.

Now, aside from poetry, I also began reading novels. I had a taste of Tokutomi Roka’s story “Nature and Life” from my school textbooks. I then read another story by him and after that read his autobiography A Record of My Memories and was moved. Then I entered the world of Russian literature through the translations of Noborishomu. I received many different impressions from this literature. Now in my old age, the feelings I had when reading those books are like a faint dream and have faded from memory. However, at the time, the feelings were of a burning passion, and in some way needed to be expressed. A group of us put together a literary magazine of our own. I became its chief editor. Takeyoshi Masanori, Imai Tomoaki, and Okamoto Yoshitake were on the editorial board. We all agreed on the name of the magazine, which was “Puppet.” We took the name from Akutagawa Ryunosuke’s story “The Puppeteer,” in which there was a line Humans are only puppets strung up and manipulated by the gods of fate. The line reflected Akutagawa’s fatalist philosophy and it was in this context we used the name for the title of our magazine.

Toshiro Saito in later life

This passage was published in Ricepaper magazine in 2013 and I am grateful to the editors there and those at Historic Joy Kogawa House.

I realize now that contracting the Spanish flu really changed my grandfather’s focus from sports to the literary when he was a teenager. He went on to work on that literary journal until 1923 when the Kanto great earthquake hit (he was editing with his friends in an upper room on impact).

I told Michiko, my aunt who helped translate the memoir, that this passage on my grandfather’s illness would go up on the Kogawa House blog and she was delighted to hear it; we didn’t know he had contracted the illness at all until we translated it although we knew he suffered from respiratory problems all his life since his youth, and he was very careful about his health ever afterwards.

—Sally Ito